Sharing Primary Sources on Twitter

To experiment with new ways to share history online, we created a Twitter account that publishes excerpts from Texas runaway slave advertisements, along with links to the page images of the ad in the Portal to Texas History.

Rationale

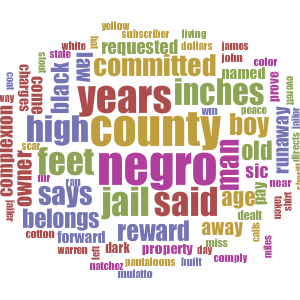

Unfortunately, the primary sources on slavery in the United States are limited. These sources are usually written from the perspective of the slaveholder and often reduce slaves to their monetary value. This can make it difficult for historians to learn about the personal experiences, attitudes, and relationships of enslaved men and women. Among these primary sources, runaway advertisements offer one of the best glimpses into the names, personalities, and experiences of individual slaves, as well as into the institution of slavery as a whole.

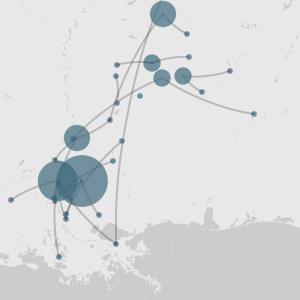

It was in the slaveholder’s own interest to provide as detailed and accurate a description of the runaway as possible, often including descriptions of slave appearance, mannerisms, and relationships. They also often include the owners’ speculations as to where the slaves might have escaped to, as well as when they ran away. All these data points can be analyzed together to create larger pictures of life at the time by mapping escape destinations, identifying seasonal trends in labor, and drawing up profiles of slave lifestyles in different areas over time.

Most of all, these runaway ads offer a valuable picture of the struggle for human liberty made by individual enslaved men and women in the nineteenth-century. Of course, the advertisements must be taken with a grain of salt, since they are written from the biased perspectives of the slaveholders attempting to recapture their human property. Nevertheless, runaway ads are one of the most detailed and long-standing forms of historical documents about enslaved people. They can help us answer questions about how slavery operated and what forms of resistance were available to slaves.

But why put these ads on Twitter? Since people often go to Twitter to relax and read funny tweets, it may initially seem odd to encounter a sobering subject like slavery in the middle of a feed. On the other hand, seeing ads in this context may help to convey the prevalence and the everyday nature of the ads in nineteenth-century newspapers. When looking for ads, students noticed that nineteenth-century newspapers often contained lighthearted poems, humorous stories, or notices of local events.

To twenty-first-century readers, one of the disturbing aspects about these ads is how they are mixed into the rest of the newspaper in such a mundane way. By publishing our ads mixed into a Twitter feed, among all the jokes and day-to-day updates, we hope to communicate both the jarring effect on students of finding the ads initially, and the familiarity that made white nineteenth-century readers see the advertisements as a normal feature of their world.

The collection of digitized runaway slave ads is extensive, and with some exceptions, largely untapped. With a large community of readers, the project might help surface ads significant to some individuals, historians, and institutions who might not otherwise have discovered the relevant source(s). For example, in creating the Twitter bot, we stumbled upon a previously unknown advertisement listed by William Marsh Rice, the founder of Rice University. The advertisement reveals valuable information –– the name of one of Rice’s slaves –– that was not even included in his census information. We hope that with the broad reach of Twitter, more ads will be unearthed that are of value to historians.

In order to connect with present-day readers on an immediate level, we decided to add an “on this day” feature to some of the tweeted ads. Inspiration was taken in part from Twitter feeds such as Civil War Day by Day. In a historical Twitter feed, posting the ads on the day of the year they were actually published can help make 100+ year-old events feel more present. Furthermore, an “on this day” hashtag fulfills one of our initial goals of surprising viewers with the ads as they browse Twitter. Systems of tagging such as #OTD or #onthisday expose the tweets to more Twitter users than just our group of followers, potentially prompting others to learn more about the sobering implications of these daily newspaper ads aimed at recapturing escaped human property. Finally, from a standpoint of social media strategy, we hoped that, by tagging the posts, we would gain followers and spread awareness both of the TxRunawayAds project and of our larger project with Texas runaway ads. After all, we are excited about our project and its findings, and want to share it with as large an audience as possible.

Methodology

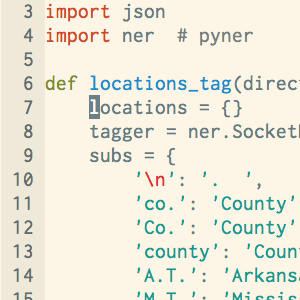

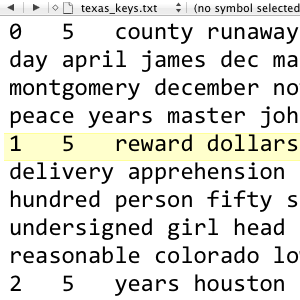

Our Twitter account publishes excerpts from runaway advertisements using Python scripts written with the help of a tutorial by Jeff Thompson.

Our first Python script, adbot.py, randomly selects an advertisement from among about 400 ads published in the Houston Telegraph and Texas Register and the Austin State Gazette between 1835 and 1860. It then publishes a new tweet containing an excerpt from the beginning of the ad and a link to the original ad, like this:

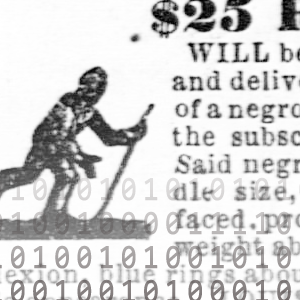

“$25 REWARD.–Ranaway from the subscriber on the 13th January inst. a negro man named Lem or Lemuel, his height…” http://t.co/wKvHHckpGZ

— Texas Runaway Ads (@TxRunawayAds) April 17, 2014

Our method of storing our data makes it easy for the script to recompose the permalink to the original ad because all of the unique information about the URL is contained in the filename of each Texas advertisement in our dataset.

Our second Python script, adbot-otd.py, also takes advantage of the fact that each ad’s filename contains the date on which it appeared. This script locates files in our dataset that appeared on the current day and then publishes the link to the ad with the original year it was published and some hashtags, like this:

#OnThisDay in 1855, this ad appeared in #Austin #Texas http://t.co/ySEQmLrp3D #OTD #ATX

— Texas Runaway Ads (@TxRunawayAds) April 21, 2014

Each of these scripts are run automatically once a day using a Mac OS X program called launchd, which was configured with the help of a tutorial by Nathan Griggs. Our adbot.py script typically runs every morning, after which the advertisement just tweeted is moved to a different directory to prevent repeated tweets. The adbot-otd.py script runs in the afternoon and posts to Twitter if there is an ad whose date matches the current date.

Currently, the Twitter feed draws on a dataset of approximately 500 ads found in three Texas newspapers: the Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston), the State Gazette (Austin), and the Northern Standard (Clarksville).

Conclusions

Our TxRunawayAds project is one of many Twitter feeds that tweets primary source material such as quotes or pictures. As Vanessa Varin notes, historical Twitter feeds are a popular and growing genre of social media, but also a problematic one. It is all-too-easy for a photoshopped or misattributed Tweet to take off, spreading historical misconceptions each time someone hits the retweet button.

In light of this, historians advise historical tweeters to always include important information about date and source attribution in their tweets. Luckily for our project, the Portal to Texas History makes it very easy to create a permalink to digitized scans of the primary source material. Social media can be a valuable resource for historians to engage with people in a non-academic setting, but it is important to keep in mind the necessity for accurate historical information even in the informal world of Twitter.

In the future, we hope to expand our source size so we are able to tweet unique ads for a longer time before recycling back through the ads already tweeted. As we alluded to in the Rationale, gaining followers also poses a major hurdle for the Twitter project. We have taken several steps to attract followers, including retweeting on personal accounts and utilizing hastags. We have seen some gains in the follower count, and moving forward we hope to continue brainstorming ways to raise awareness of our project, such as through the use of different hashtags to introduce the ads to a more diverse audience. Through this challenge of publicity, our Twitter feed exemplifies the fact that even after clearing all the technical challenges to create a digital history project, promoting the project remains a separate problem.