DIGITAL HISTORY METHODS

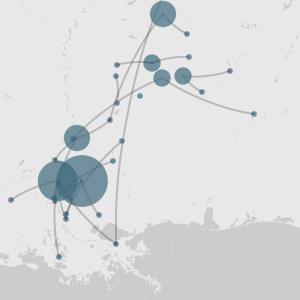

can help historians understand and present the past by supplementing traditional techniques for reading historical sources like newspapers and runaway slave advertisements.

can help historians understand and present the past by supplementing traditional techniques for reading historical sources like newspapers and runaway slave advertisements.

As students and scholars in the Spring 2014 course Digital History Methods at Rice University, we created this site to showcase a few digital history methods, using a sample data set of nineteenth-century runaway slave ads. Click on these thumbnails to learn about our methods, or read more about our data below.

Our Data

We have applied these methods to a specific kind of historical source: runaway slave advertisements from the antebellum U.S. South. Our ads are drawn from two sources. First, in collaboration with students in Dr. Andrew Torget’s digital history class at the University of North Texas, who have published some of their own findings and methods on a research blog, we identified and transcribed all runaway ads published between 1835 and 1860 in two Texas newspapers that have been digitized on the Portal to Texas History—the Telegraph and Texas Register, published in Houston for most of its run, and the State Gazette, published in Austin. We also analyzed advertisements from Arkansas and Mississippi that were transcribed as part of the Documenting Runaway Slaves project at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Before analyzing these sources, we first used digital tools to create one text file for each advertisement in our corpus. Each file’s content was comprised exclusively of transcribed text from the ad. We used the filename of each text file to store relevant metadata such as when the ad was published and where.

Our project conforms to the fifth tenet of the Unix philosophy: Store data in flat text files. That is, before using any of the methods described on this site, we created a corpus of ads in which each advertisement got its own text file.

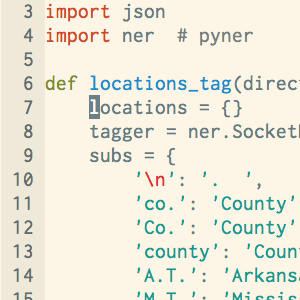

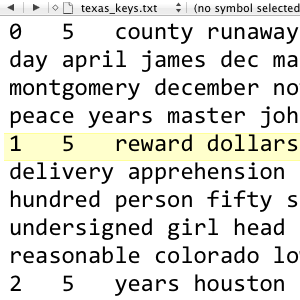

Information about ads from Texas newspapers—including transcribed text, date published, newspaper title, and a permalink URL to the ad’s image in the Portal to Texas History—were first collected in a Google Drive spreadsheet shared by students at Rice and UNT. After downloading each sheet of ads in CSV format, we then used a Python script to turn every unique transcribed ad (excluding reprints) into a file whose name looks like this:

TX_18430705_Telegraph_67531-metapth48242-m1-3-8502-3469.txtwhere the first two letters represent the state in which the ad was published, the eight-digit string after the first underscore represents the date of publication in YYYYMMDD format, the string after the second underscore represents the abbreviated title of the newspaper, and the hyphen-separated strings after the third underscore represent unique information drawn from the permalink to the page image containing the ad in the Portal to Texas History.

Ads collected as part of the Documenting Runaway Slaves are currently made available in rich-text PDF files containing all Arkansas ads and all Mississippi ads. To burst these files into individual text files, we first used some native Mac tools and regular expressions to extract and clean up the text from the PDFs, placing them all in a single text file for each state. Another Python script then allowed us turn those cleaned text files into individual advertisement files whose names look like this:

AR_18631118_Washington-Telegraph_18631118-489.txtwhere the first two letters represent the state in which the ad was published, the eight-digit string after the first underscore represents the issue date of the newspaper in which the ad appeared, transformed into YYYYMMDD, the string after the second underscore represents the title of the newspaper, and the string after the third underscore represents the date that serves as a header for each new ad in the Documenting Runaway Slaves PDF followed by a hyphen and a unique ID generated by the Python script.

Storing our data in this way made it easy to regroup and recombine ads according to different criteria using simple bash commands, shell scripts, or graphical programs like the Finder in Mac OS X. Files could easily be sorted in chronological order or by other fields stored in the filename. Having the ads already split into small text files enhanced the performance of several of the digital tools we used, like MALLET and NER. And using information contained in the filenames, we were also able to use additional scripts to count ads by year, month or day or to excerpt and Tweet ads.

A Note on Our Sources

Readers of these pages should keep in mind two important facts about the runaway slave advertisements we used in our digital history experiments.

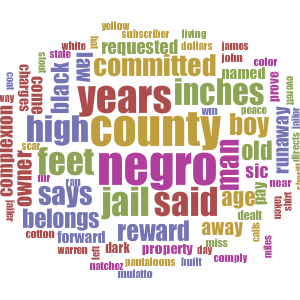

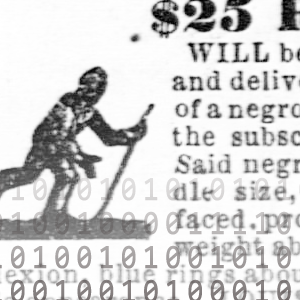

First, these historical sources often use nineteenth-century language about race and slavery that would be offensive if used today. We have preserved the use of words like “negro” and dimunitive words like “boy” in our transcriptions and visualizations because these words were used by the authors of the original advertisements.

We also urge readers to notice that most of the digital methods profiled here treat our runaway ads in aggregate. More traditional methods like “close reading” would likely reveal a different, but not incompatible, picture of slavery from the methods showcased on this site—one more reflective of the diverse individual and local experiences that made up the history of American slavery.

As art historian Marcus Wood has observed, the Southerners who created these runaway advertisements wanted to deny the individuality of enslaved people (by considering them all as so much property with dollar amounts attached to their names), but the ads also allow us to glimpse individual lives. “The advertisements embodied the hard-nosed business approach of owners to the loss of valuable property” and “remained largely standardised” (Wood, 80). But the ads also worked against the writers’ intentions by providing “a perpetual catalogue of the abuse of the slave body” and the actions taken by enslaved people to escape that abuse by “confronting and opposing the authority of their owners” (Wood, 81; Camp, 36).

One limitation of our digital methods may be their inability to capture in full detail those day-to-day abuses and struggles. Our method of sharing ads on Twitter may provide the best window into that catalogue of struggles between individual owners and the people they claimed as slaves, while our other methods provide a more abstacted look at runaway slave advertisements as a whole. For the most part, our project focuses on the presentation of digital tools; for a clearer understanding of the personal struggles of slaves, see a close reading such as the one by John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger.

Bibliography

Ashton, Susanna, and Jonathan D. Hepworth. “Jackson Unchained: Reclaiming a Fugitive Landscape,” The Appendix, November 5, 2013.

Camp, Stephanie. Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Campbell, Randolph. An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas. Baton Rouge: Lousiana State University Press, 1989.

Carrigan, William Dean. “Slavery on the Frontier: The Peculiar Institution in Central Texas,” Slavery and Abolition 20, no. 2 (1999), 63-96.

Cornell, Sarah. “Citizens of Nowhere: Fugitive Slaves and Free African Americans in Mexico, 1833-1857,” Journal of American History 100, no. 2 (2013), 351-374.

Franklin, John Hope, and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Kelley, Sean. “Blackbirders and Bozales: African-Born Slaves on the Lower Brazos River of Texas in the Nineteenth Century.” Civil War History 54.4 (2008): 406-23.

Wood, Marcus. “Rhetoric and the Runaway: The Iconography of Slave Escape in England and America,” in Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780-1865 (New York: Routledge, 2000), 78-94.

Acknowledgements

This site was built by Dr. Caleb McDaniel and six undergraduate students at Rice University: Alyssa Anderson, Franco Bettati, Aaron Braunstein, Daniel Burns, Clare Jensen, and Kaitlyn Sisk. Maria Montalvo also assisted with page checking and the collection of advertisements. We would like to thank Dr. Andrew Torget and his students at the University of North Texas for sharing data with us, as well as Dr. Max Grivno, Dr. Douglass Chambers, and the team behind Documenting Runaway Slaves at the University of Southern Mississippi. Please send questions to , or comment and open issues on our GitHub repository.